Stories We Need to Hear: The Use of Anecdotes in Black Composer Histories

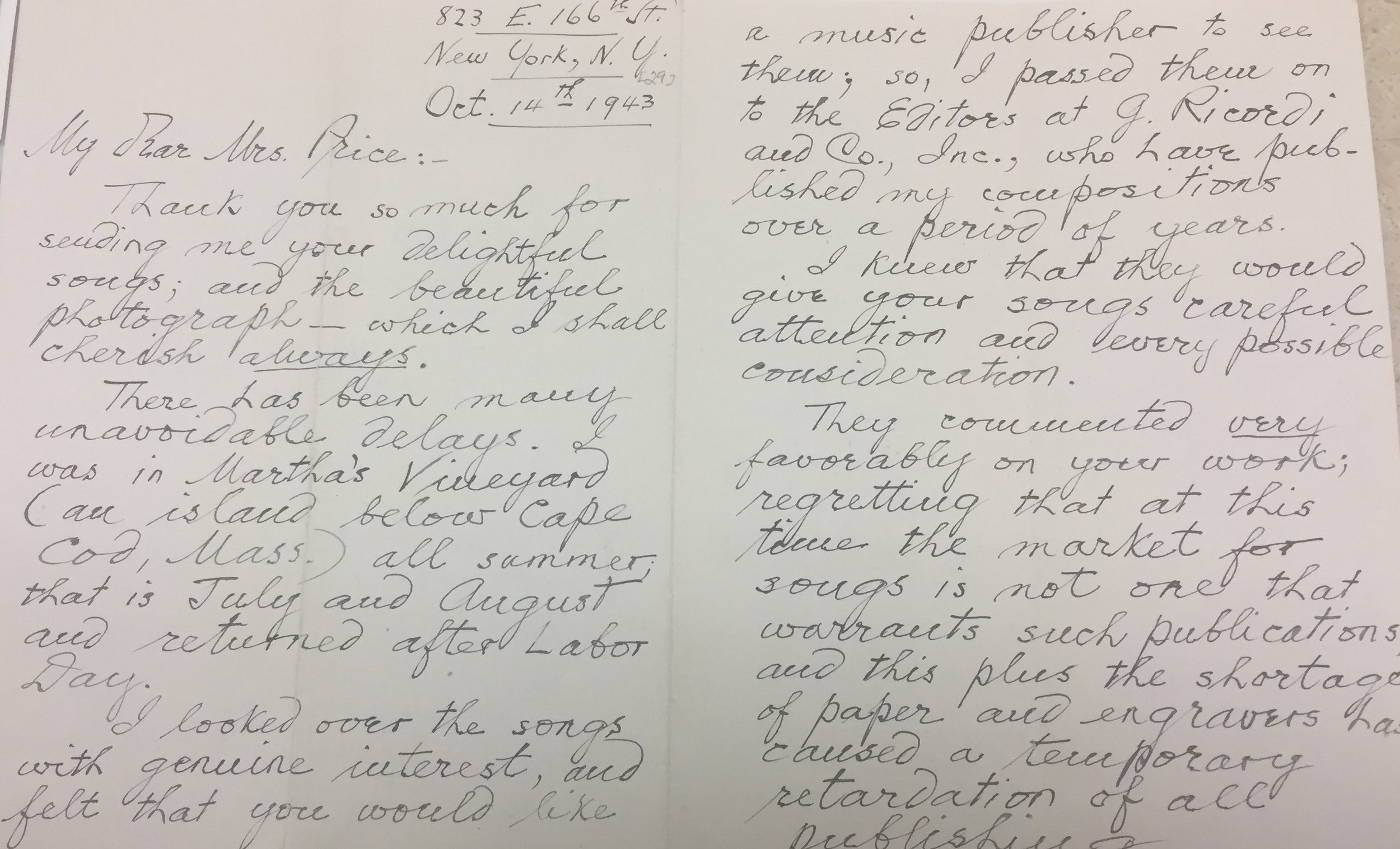

Letter from Harry T. Burleigh to Florence Price, 1943. Florence Price Papers Addendum, M988a, University of Arkansas-Fayetteville

The year is 1943. Harry T. Burleigh has finally completed his letter to Florence Price, taking him around two weeks to write. The document contains many topics, most notably Burleigh’s receipt and forwarding of Price’s art songs to G. Ricordi and Co. The publishing house declined the pieces, but Burleigh continues with his own thoughts on Price’s compositions:

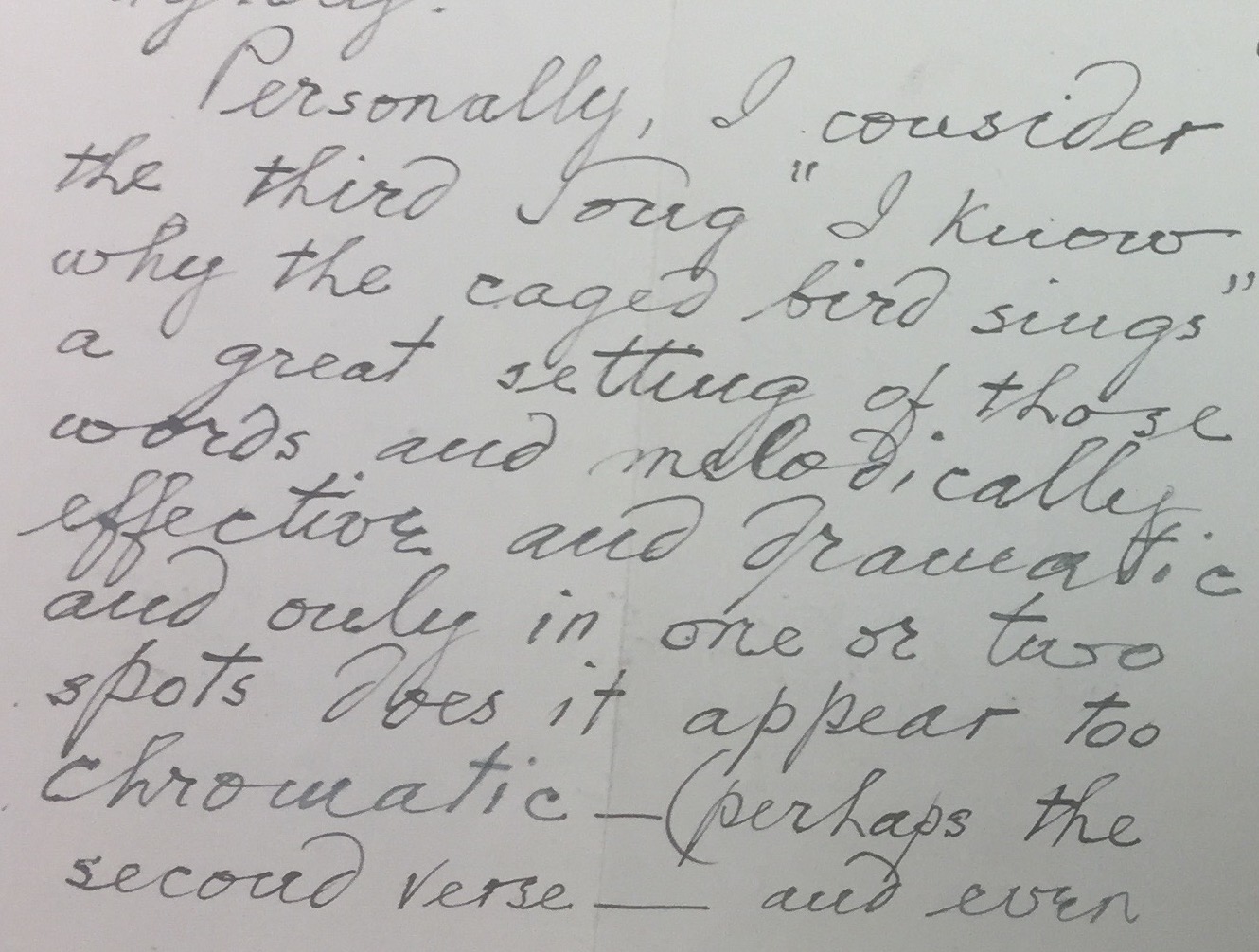

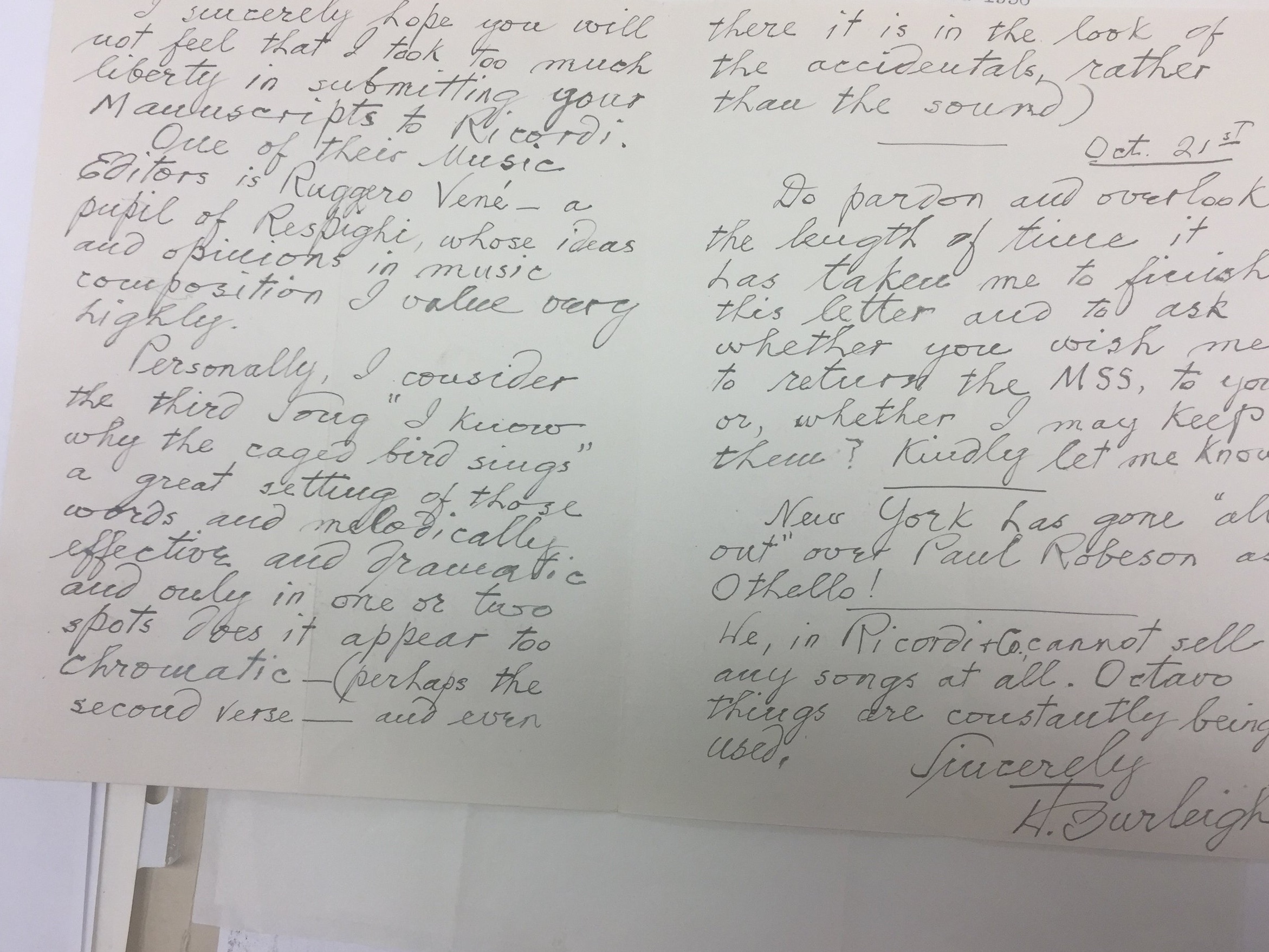

“Personally, I consider the third song “I know why the caged bird sings” a great setting of those words and melodically effective and dramatic and only in one or two spots does it appear too chromatic – (perhaps the second verse – and even there it is in the look of the accidentals, rather than the sound).”

It is currently unclear how Price responded (if her response still exists). Was she miffed that Burleigh forwarded her pieces without her permission? Appreciative? Did she apply changes to the “too chromatic” areas or keep them as is? There are numerous questions this letter could prompt, not only in relation to Price’s hypothetical response, but to issues related to style, support networks, and how we talk about the careers of Black composers.

It’s these types of stories that I love to read and use as a window to other questions about composers’ lives. Anecdotes, whether we read them or hear them from fellow musicians, may be used to illuminate our understanding of the music we love and the people who make it. Some of the most insightful details on Burleigh, Price, and other Black composers that I’ve learned were not always written down: they were via conversations over coffee, over the phone, or between panels. The historical figures took on a shape that is not always possible within the types of narratives used for classical composers. Rather than recreate a static account of these individuals, I want to see stories that allow their opinions and personalities to take center stage in their messiness and complexity.

But studies of Black classical composers still require a larger collection of published biographies and analytic studies. Burleigh , but Price’s first book- length monograph is still forthcoming, and a number of their contemporaries only have article-length biographies and encyclopedic entries. and are two of the most published of historical Black composers, and in Still’s case was the result of fierce preservation work by himself, family members, performers, and scholars.

The genre of music biography has been receiving needed these last few years. And yet one of the purposes of biography: telling the reader when and where the subject lived their lives and built their career is still sorely needed in studies of Black classical composers. We need to know how Burleigh’s career path put him into contact and friendship with major figures (Marian Anderson, Roland Hayes, etc.); we need to know he was a supporter and competition judge for the . From this, we learn that Burleigh recognized the importance of mentorship and networking with younger Black musicians as a tool for institutional stability, providing creative, educational, and financial support and recognition of their artistry due to their systemic exclusion from the white mainstream.

So how may this Burleigh-Price letter take us outside of the purely biographical? First, it can help us in our construction of their stylistic personalities; chromaticism was not anathema to Burleigh, but if we study his use of it in his art songs, will we see a wildly different application compared to Price’s art songs? Rae Linda Brown observed similarities in Burleigh and Price’s treatment of text, but how did their diverging choices make an art song/concert spiritual distinctly theirs? Thanks to the published biographical work on Burleigh and Price, we may use that material with this correspondence to address these stylistic questions and consider the creative stimulus such interactions supplied..

, and the latter made a point to program her vocal music on his recitals. Price’s comfort in sending Burleigh her unpublished songs and Burleigh’s comfort in getting them published on her behalf reinforce their interaction was not just a matter of two big names in Black classical music history having moments of contact; as her senior, Burleigh made it a point to help get her music to audiences via concerts and publication. When you consider the forms of camaraderie and support Black composers needed to get their music performed and published, it shows that of biography and analysis are required to do their lives justice.

This is the first part in our exploration of the ways anecdotes can lead us to specific musical and cultural answers related to Burleigh and his world. Next month, we’ll continue this discussion of Burleigh’s and Price’s approaches to art song via the piece featured in this letter, renamed “Sympathy” and .

Letter from Burleigh to Price, 1943